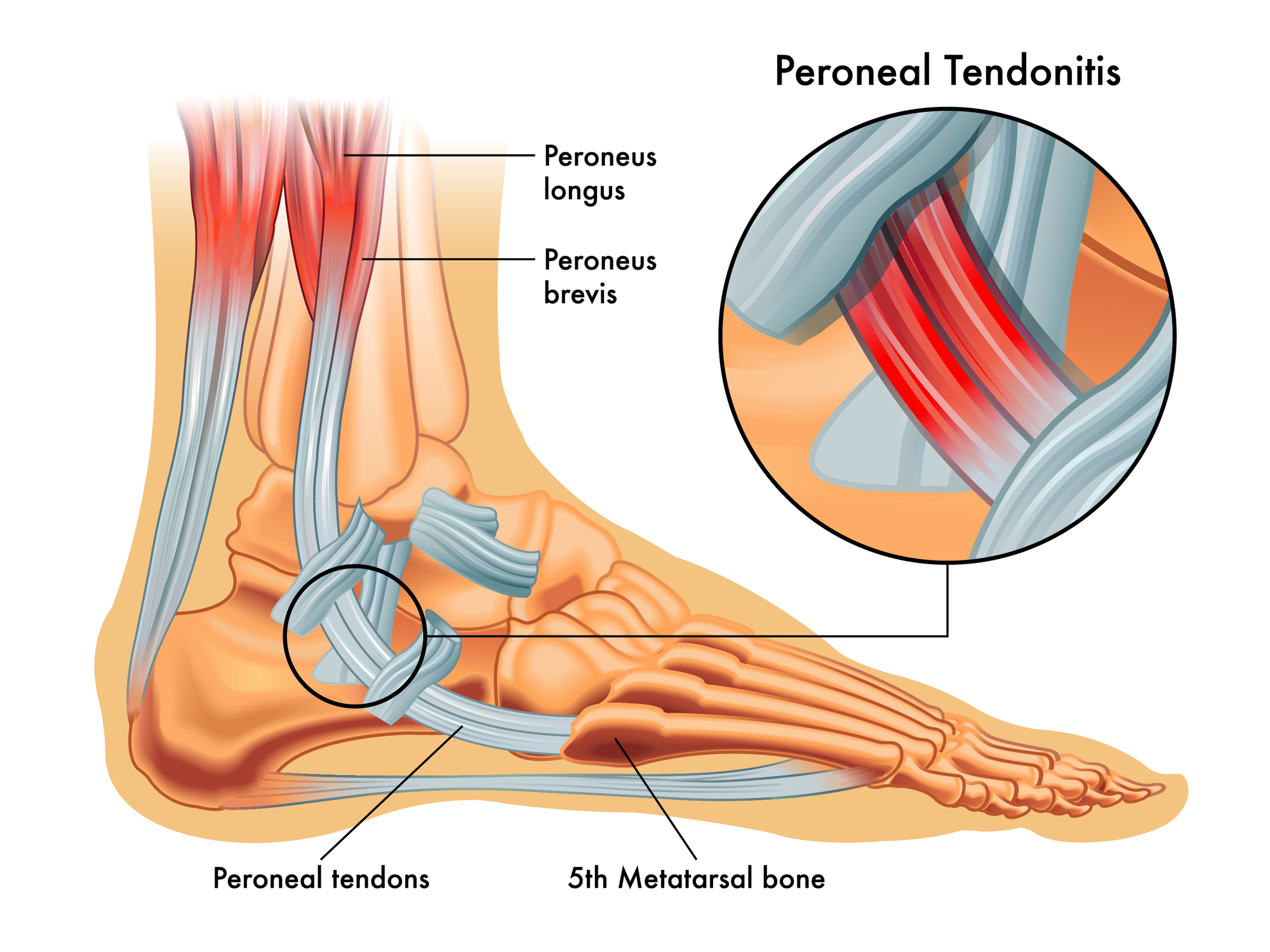

Peroneal tendonitis is a somewhat uncommon overuse injury of the peroneal tendons on the outside of the ankle joint. The peroneal muscles are two muscles (peroneus longus and peroneus brevis) that are on the outside of the leg. The tendons from these muscles go around behind the outside ankle bone (lateral malleolus) and then forward into the foot where the peroneus brevis inserts into the base of the fifth metatarsal and the peroneus longus passes under the foot to insert into the medial side of the arch of the foot.

Signs of peroneal tendonitis

The symptoms of peroneal tendonitis are a slowly increasing pain in the peroneal tendons either just above or just below the outside ankle bone (lateral malleolus). The pain is worse on activity. There may sometimes be some palpable swelling in the area.

Causes of peroneal tendonitis

The cause of peroneal tendonitis is pretty much the same as any other tendinopathy: the cumulative loads are greater than the tendon is adapted to be able to tolerate. There are three parts to this: the loads and what the tendon is adapted too and tendon vulnerability.

- The Loads:

The load on a tendon is a function of two variables.

a) The volume and intensity of training done: If this is high, then there is more load on the peroneal tendon and it is at risk for an overuse injury (if it is not adapted to those loads).

b) Biomechanical factors: There are increased loads on the peroneal tendons if the supination resistance is lower (the foot is easy to supinate, so the peroneal muscles work harder) or the subtalar joint axis is deviated more laterally (the peroneal tendons will have a shorter lever arm to pronate the foot, so the muscles have to work harder). For runners, a forefoot strike pattern puts a greater load on the peroneal tendons. - What the tendon is adapted to:

Tendons are designed to take loads, but if the cumulative loads on them is increased and they are not given time to adapt to those increasing loads, then there is an increased risk for a peroneal tendonitis to develop. This is the good old fashioned saying of “too much, too soon”. Training loads need to be increased gradually and slowly with adequate rest so that the tissues can be given a chance to adapt to the increasing loads. - Tendon vulnerability:

The issue here is nutritional status and general health. Deficiency’s and various general health statuses (eg hyperlipidemia) make the tendons more vulnerable to damage.`

Treatment of peroneal tendonitis

The key to the management of peroneal tendonitis is to manage the symptoms and manage the loads, then facilitate the healing if its not responding to the load management. Attention needs to be directed at any dietary or nutritional issues.

Manage the symptoms:

If the pain is a problem, then activities need to be reduced to what is tolerable or alternative activities considered (eg cycling or swimming). ICE can be used after activity to help with the pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (eg ibuprofen, diclofenac, celecoxib, acetaminophen) may be used.

Manage the loads:

a) Training loads:

These need to be reduced down to what is tolerable. Tendons still need some load going through them to help healing, but not too much so that it increases the tissue damage. As the symptoms decrease, the intensity and volume of training is slowly but gradually increased to load the tendon. Rest is extremely important to allow tendon to adapt to the loads before the next load is applied.

b) Biomechanics:

For runners a higher drop running shoe or a heel raise will help reduce some load in the peroneal tendons. This need not be permanent and can be short term measure and transition away from it as the symptoms improve.

Lateral wedging under the heel is one of the most effective way to biomechanically reduce the load in the peroneal tendons. This can be a wedge on it own or a lateral wedging design feature incorporated into a foot orthotic (eg a lateral Kirby skive).

Facilitate the healing:

If the symptom management, load management and biomechanical interventions are not producing the desired changes or the problem has become somewhat chronic then interventions such as shock wave therapy and injection therapies may need to be considered. The primary aim here is to facilitate the healing of the tissues in the tendon. These types of interventions may not be as helpful over the longer term if the load and biomechanical issues are not also addressed.

Exercises for peroneal tendonitis

Exercises are widely and commonly recommended for peroneal tendonitis, but I remain unconvinced that they are actually any use.

There are stretching exercise that can be done for the peroneal muscle/tendon complex, but as a tightness of these structures are not a factor in peroneal tendonitis, I fail to see how stretching them will help.

There are strengthening exercises that can be done for the peroneal muscles, but a weakness of these muscles has not been identified as a factor in peroneal tendonitis, so I fail to see how strengthening them will help. Sometimes there appears to be quite an apparent weakness of the peroneal muscles, but all of those that I have seen were due to either a peroneal inhibition or a laterally deviated subtalar joint axis (the peroneal muscles will appear artificially weak to eversion testing because of the shorter lever arm they have to the joint axis, so aren’t weak at all but are quite strong).

HOWEVER, having said that, stretching and strengthening exercises do put a load on the tendon and may be helpful at conditioning the tendon because of that, but not becasue they stretch the tendon and strengthen the muscles. I am happy to be convinced otherwise.

Forum discussions on peroneal tendonitis

Peroneal tendinosis and ankle sprains

Peroneal muscle inhibition

Asymptomatic peroneal tendon pathology

Personal opinion on peroneal tendonitis

Clinically, I do not recall ever seeing a peroneal tendonitis issue that did not have a lower than average supination resistance – that is since I was aware of the concept and knew what to look for. I wrote here, about our study we did on this to confirm that clinical impression. It makes sense why as those with a lower supination resistance are much more easy to invert making the peroneal muscles work harder. Combine that with some training load issues and the tendons get a bit overcooked resulting in the peroneal tendonitis.

I also recall that my clinical experience prior to that research with peroneal tendonitis was somewhat frustrating and always a challenge to manage with a lot not doing too well. During the study I linked above, it was pretty obvious early on that the clinical impression of low supination resistance was the issue. I also recall the first clinical case of this that I got after that study. It was a long term chronic case that nothing else seemed to be able to help. Based on the results, I went straight to a lateral heel wedge to treat it. I will never forget that almost immediate clinical response to doing that – it was most gratifying. This is a story I frequently tell in my Clinical Biomechanics Boot Camp Courses. I like talking about how research changes my clinical practice.

Author:

University lecturer, runner, cynic, researcher, skeptic, forum admin, woo basher, clinician, rabble-rouser, blogger, dad.